What has baffled me most throughout my

academic and professional career is the concept “African Dance.” In a world in

which almost everything is framed in the idiom of the market, the concept ‘African

Dance’ has proven particularly compelling. Widely used by academic institutions,

arts organisations, dance companies and troupes, scholars, teachers,

performers, and a wide range of arts practitioners, this concept is still craving

for a comprehensively laid out explanation. In an attempt to find an accurate rationalization

of what is and what is not ‘African Dance’, I have bounced the question: ‘What

is African about ‘African Dance’?’ to a range of people, including continental

Africans.

The answers that I have received in response to

the above question are as varied as the people that I have consulted. In fact,

the responses have raised more questions than answers. A number of these responses

are just a regurgitation of what some scholars have posited as “characteristics

of ‘African Dance’” – use of the drum, circular formation, poly-rhythmic, orientated towards the

earth, improvisation, isolation of body parts, etc.

This lack of explanatory intelligibility makes the concept ‘African Dance’ resemble the biblical tower of Babel, which builders failed to complete because they started speaking different languages-tongues.

The questions that arise from this conceptual

ambiguity are: Why is the concept ‘African Dance’ a mystification? If the

concept ‘African Dance’ is too succinct, how deep is its impact?

It appears the coining of this concept was based on the assumption of universalism of knowledge and cultural practices in Africa. Theorization of dance and music practices from cultures in Africa was anchored in the sense of “’horizontal fraternity’, itself imaginatively embedded in fiction of cultural homogeneity” (J.L. Comaroff & J. Comaroff, 2009). Artistic relativism and ethnic heterogeneity was disregarded. Yet, Africa as a continent is a collection of heterogeneous demographics, and not a homogeneous entity. It is estimated that Africa is composed of more than 3000 tribal and sub-tribal communities, with each tribe boasting of a range of cultural practices that are poles apart.

The miscellany of ethnicities and

sub-ethnicities translates into multiplicities of music and dance traditions

that are distinct from one another and unique to these particular communities. As Judith

Lynne Hanna appositely attests, “Africa

has about 1000 different languages and probably as many dance patterns. Dance

styles vary enormously and so do definitions of dance. For example, among the

Ibo, Akan, Efik, Azande, and Kamba, dance involves vocal and instrumental

music, including the drum, whereas among the Zulu, Matabele, Shi, Ngoni,

Turkana, and Wanyaturu, drums are not used, and sometimes the users of drums

are despised.” Therefore, to clamp these culturally diverse dance forms into

one umbrella – ‘African Dance’, was bound to create ontological, epistemological,

axiological and etymological challenges in the study and practice of dance

forms from cultures in Africa.

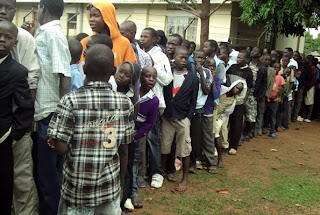

Karimojong people of North Eastern Uganda performing one of the traditional dances. The drum is not common in dances of the Karamojong people.

The notion that ‘African Dance’ is ‘African

Dance’ was exacerbated by the actuality that most of Africa’s pre-colonial,

colonial and post-colonial cultural history was written and documented by habitually

non-Africans. And frequently, early European observers of African behavior did not consider African dance to be dance, for it was not the familiar classical ballet or foot-tapping folk dance of their home countries (Hanna, 1973). This history cannot be wished away for it forms and informs the

current academic, literary and artistic discourses and trajectories. Whereas writing about cultural history might

seem to be mere chronicling of events, circumstance, experiences, stories and instances, the

interpretation and consumption of ethno-commodities by the writer (consumer),

and its conversion into literary work is as imperative. In the process of

writing, these commodities are re-processed, re/mis/interpreted, and misrepresented. In this instance, theorization of

vernacular dance forms from cultures in Africa suffered latent and manifest

orientalism, which gave birth to contemporary artistic orientalism.

The first researchers, writers and teachers

of dances from cultures in Africa were mostly Europeans and North Americans. Moreover,

they were anthropologists, ethnomusicologists and sociologists – not dancers. According to Mazrui (2002), our understanding of Africa and its past has been bedeviled by reports written by imaginative European travelers throughout the continent. Predictably,

their analysis, conceptualization and interpretation of cultural identities in

Africa was more ‘Americentric’ and Eurocentric than ‘Afrocentric’. Not even their ethnographic approaches to scientific and non-scientific discovery could

deliver clarity and details encompassed in dance practices from cultures in

Africa! In many ways, the recollection of past events, passed on by word of mouth in Africa today, may be a better guide than the vivid and romantic accounts of some of the European explorers (Mazrui, 2002).

In this Western-oriented literary trajectory, the content generated about dances from Africa fell prey of a noteworthy scale of confirmation, intellectual and cultural bias;

and the ensuing knowledge de-Africanized. Cognizant of the fact that “Africans

are a people of the day before yesterday and the day after tomorrow"

(Mazrui, 1986), what must concern us is the history of the present. Or, more

specifically, its effects: how is it alternating the comportment in which

artistry, scholarship and teaching of dances from cultures in Africa is

experienced, philosophized, conceptualized, re-theorized, comprehended,

ratified, and represented.

‘African Dance’ is just an imagined concept.

It is a sheer geographical expression than a representation of multicultural existentialities

and artistic, creative and aesthetic dualities that are replicated in the

diverse dance and music traditions. Max Beloff reminds us that 'it is easier to understand the contiguities of geography than continuities of history.' The generalization of African dances has ensconced a subterranean

and stereotypical fallacy that Africa is not a continent with mottled

demographics but a single identical entity. If we are convinced that the

concept ‘African Dance’ is valid, why don’t we have ‘European dance’ or ‘American

Dance’ or ‘Asian Dance’ as styles of dance?

The concept ‘African Dance’ is begging for

lucidity. Revisiting this notion is logical, and redefining it most apt. It is our duty as teachers, researchers,

trainers, scholars, performers and instructors of “Dances from Cultures in

Africa” (emphasis) to unravel this historical distortion, deconstruct this

nebulous concept and the mindset that it has fashioned.

Modifying the concept ‘African Dance’ to

‘Dances from Cultures in Africa’ can be a good starting point in providing this

long awaited clarity, which will assist these

art forms to claim their rightful place in modern and global civilization.

Alfdaniels Mabingo is a Fulbright Fellow at New York University

.jpg)